CHINA’S LIMITED REACH

China’s limited reach

A recent TDF webinar discussed the extent, and limitations, of Chinese interests in South Asia

As many nations experience China’s increased engagement in their economies and societies, The Democracy Forum shone a spotlight on China’s role as a primary source of development finance in South Asia, at a virtual seminar titled ‘China in South Asia: Investment or exploitation?’

The webinar’s remit, said TDF President Lord Bruce, was to consider if China is following a broadly positive programme of investment in public infrastructure to spread the benefits of economic growth or, conversely, if it is pursuing a process which may amount to colonialism by default.He spoke of the steady accumulation of Chinese foreign direct investment, citing an article in the Economist, which concluded that the world now owes China’s eight largest state-owned banks at least $1.6trm – equivalent to 2% of global GDP. Vis-à-vis investment versus exploitation, Lord Bruce highlighted that China is currently pursuing a ratio of loans to grants in the order of 31:1 priced at relatively high interest rates, although around 36% of all loan programmes started under the Belt and Road Initiative since 2013 have encountered ‘implementation problems’. He also touched on Chinese loans and arms supplies to Bangladesh and the diplomatic leverage Beijing might expect to exert from this relationship, as well as Sri Lanka’s accumulated loan obligations to China, which have reached 20% of its total public external debt, and how China is Pakistan’s biggest bilateral creditor, holding $30bn of its total debt, with Pakistan additionally hobbled by the contractual obligations it has accumulated under the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC).

China’s money ‘goes to two kinds of borrowers; those with a good chance of repaying (either because projects are likely to turn a profit or governments are sufficiently rich), or those for which any lost money represents a price worth paying for diplomatic advantage’, according to The Economist. In the case of South Asia, Lord Bruce concluded, it looks as if China’s international development criteria will always favour the second category of borrower.

Chinese involvement in South Asia’s security complex is a growing reality, evolving and multi-dimensional, argued Dr Frédéric Grare, Senior Policy Fellow at the European Council on Foreign Relations, who stressed the importance of considering China’s relationship with the different countries in South Asia on theirown terms, as not every country in the region feels the same way about China’s willingness to impose its hegemony over the region. Grare identified three tiers in Beijing’s approach to its security relationship with South Asia: the stability of its territory (with Afghanistan being a typical example); its rivalry with India and relationships with India’s neighbours.including Pakistan, which is by no longer the sole client of China in South Asia; and how China’s relationship with India affects India’s relationship with the US, and vice-versa. If we look at the way China has been pursuing its objectives in South Asia, said Grare, it runs the gamut of activities, from overt war (in 1962), to war by proxy(for instance in support for Pakistan and the separatist movement in the Northeast), and its role as the first supplier of weapons to Bangladesh.

Grare also spoke of China’s ‘weaponsiation’ of every sector of activity. including influence in connectivity and the environment. This plays out through the dependency question – examples arethe Maldives, the 99-year lease on Hambantota Port in Sri Lanka – and subsequent repercussions for India and the entire neigbourhood. Is China pursuing debt-trap diplomacy? wondered Grare. Not in the sense that it is deliberately trying to put countries into debt in order to better control them – there are, after all, issues of local responsibility, such as mismanagement of the economy. However, this doesnot mean China is not trying to play opportunistically on countries’ debts, and this is where coercioncan start.

Chinese involvement in South Asia’s security complex is evolving and multi-dimensional

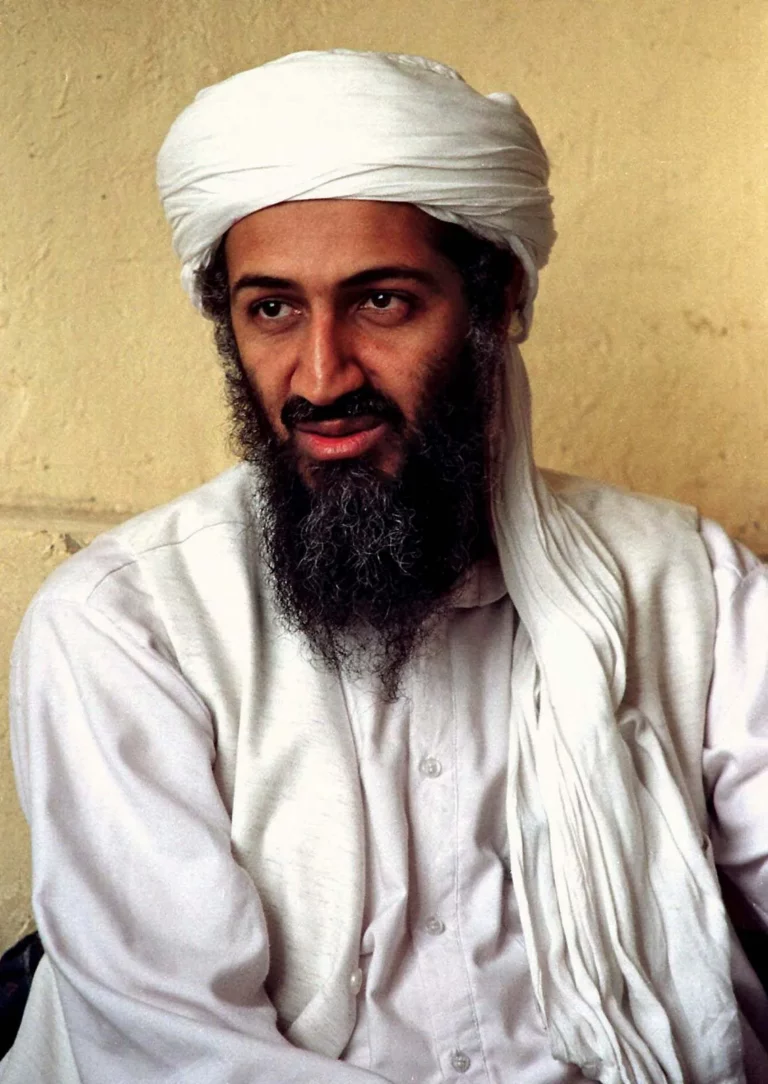

Dr C. Christine Fair, Professor of Security Studies at Georgetown University’s Edmund A. Walsh School of Foreign Service, focused on China’s role and interests in Afghanistan which, she said, date back to the Soviet invasion of the country, when China, along with other powers, were backing the mujahideen. China was supportive of its own Uyghur population going to fight the Soviets, although negative externalities ensued, with the Uyghurs returning homebattle-hardened and ‘part of the landscape of jihad’ whose narrative was that they could take on a superpower. By circa 1990, China had realised the implications of its policies, and by the mid-90s it had launched the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation, focused on countering Islamic terrorism.This was also when China really began to figure out its policy regarding the Taliban, whom it was asking to stop supporting ETIM and Uyghur separatists.

When 9/11 happened, China quickly re-optimised its strategy, backing what would be the internationally supported government inAfghanistan while continuing its support for the Taliban, though Beijing came under criticism for being a free rider under the US-NATO security umbrella. By 2007 China was the single most important actor in Afghanistan, on the brink of signing an MoU with al-Qaeda and Osama bin Laden, who never criticised China for its brutality against Uyghurs and other Muslims. With the rise of Xi, China became more interested in Afghanistan via the BRI project, said Fair, who also underscored an important but overlooked aspect of CPEC, the agricultural sector. In the long term, she argued, Pakistan’s precious water resources are being used up by the Chinee with no obvious long-term benefit to Pakistan. Ultimately, she suspected that the biggest obstacle to China’s ability to profit from Afghanistan’s huge resources is instability in Afghanistan, since the main way Islamic State Khorasan Province is trying to distinguish itself from the Taliban is by levelling its sights at China, making Afghanistan a very hard nut for Beijing to crack.

Collective punishment is used to silence dissent

By 2007 China was the single most important actor in Afghanistan

Sounding a note of cautious optimism about China’s ability to turn investment into exploitation was Dr Christopher Clary, Assistant Professor of Political Science at the University at Albany, State University of New York. While Clary had no illusions about China’s benign intentions, it is difficult, he said, to both generate economic power and use that power to achieve political ends. In highlighting the changing situation impacting China’s reach, he raised threekey points. Firstly, the BRI emerged in a specific global and economic context, which is now ending, with China going into a period of having less money as it faces a property investment bubble, higher labour costs, an ageing population and imperfect welfare state, with implications for labour participation and consequent limitations on what China can produce economically. China’s growth, therefore, may not exceed what India, Bangladesh or others can achieve, and a possible long period of accelerated Indian growth means India may have more money to invest abroad, creating an alternative to Chinese investment. Secondly, said Clary, large outside economic, social or political pressure on any society generates antibodies to that pressure, and China will not be immune to problems caused by the poor behaviour or lack of integration of its expatriate populations in, for example, Pakistan. And thirdly, he saw real limitations that emerge from Chinese investments overseas, since multipolarity will give troublesome regimes options that they lacked in prior decades.

Addressing both the magnitude and limits of China’s influence on Pakistan wasphysicist and writer Pervez Hoodbhoy, who addressed the ‘great expectations’ that CPEC would transform Pakistan’s economy, with $62.5 billion of Chinese investments in infrastructure and electricity generation bringing a new era to Pakistan’s development. Yet Pakistan is in a state of default, seeking $1.1 bn in IMF bailouts. Hoodbhoy contended that the planned development had not worked because infrastructure alone is insufficient; it must be accompanied by human capital, good governance and transparency. Where was the investment used, what were the terms of the agreement, the interest rates, he asked? Much was in the hands of the Pakistan army, which insisted on being the controlling authority of CPEC. There is no evidence of new industries sprouting up and local employment has been small. And while, to counter this, 30,000 Pakistan students were sent to China, they did not acquire the skills necessary for employability in science and engineering.

Hoodbhoy also highlighted China’s ‘invisible’ presence in Gwadar, and Pakistan army machine guns along CPEC highways, a source of resentment for the Baloch people, who feel colonised by Punjab. As for the Chinese, they are very sequestered, with little local interaction. CPEC hasn’t delivered on its promises, and Pakistan has a $30 bn loan to pay, interest unknown. Looking to the future, Hoodbhoy did not envisage Chinese influence in Pakistan growing to the extent once surmised.

Closing the event, TDF Chair Barry Gardiner said that China, like every other country, is both pursuing investment and taking advantage of any defaults through exploitation. You can form alliances but don’t mistake them for friendship, he warned. Be realistic that every country acts in its own interests, though it should be the public interest, not private interests, as seen in Sri Lanka and Pakistan.

Neville de Silva is a veteran Sri Lankan journalist who held senior roles in Hong Kong at The Standard and worked in London for Gemini News Service. He has been a correspondent for the foreign media including the New York Times and Le Monde. More recently he was Sri Lanka’s Deputy High Commissioner in London