KHAN’S DUBIOUS DEALS

Khan’s dubious deals

Following the lifting of a ban on the far-right TLP, Sudha Ramachandran considers the implications, and wonders if Imran Khan will ultimately de-proscribe another, more menacing extremist group

The Pakistan government is on a deal-making spree with religious extremist and terror groups. Close on the heels of sealing a deal with the Tehreek-i-Labbaik Pakistan (TLP), the government has agreed on a month-long ceasefire with the Tehreek-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP).Both groups had been designated as terrorist groups and figured in a list of proscribed outfits.

As per the deal with the TLP, the Imran Khan government has lifted the ban on the group, released its chief Saad Hussain Rizvi from jail and removed his name from a list of individuals designated terrorist.In addition, thousands of TLP activists have been freed from prison.

There is now concern that the government will lift the ban on the TTP as well.

While the TLP has engaged in violence over the years, resulting in the deaths of scores of people, mainly policemen, the threat that the TTP poses to the Pakistani state and its citizens is far greater. The group has implemented hundreds of attacks that have killed thousands of people. In 2014, for instance, the TTP carried out a suicide attack on an army-run school in Peshawar that resulted in the death of around 140 people, most of them children.

Analysts fear that de-proscribing the TTP, should it happen, will enable it to re-emerge as a potent force and retake control over territory.

Bitter internal fighting, American drone strikes and Pakistani military offensives weakened the TTP and, by 2014,the outfit was reduced to striking at soft targets. However, it has been making a recovery in recent years under the leadership of Noor Wali Mehsud. Factional fighting has ended and feuding leaders have returned to the TTP fold.Importantly, the Afghan Taliban’s capture of power in Kabul has provided the TTP with a shot in the arm, boosting both TTP morale and access to sanctuary in Afghanistan.

Should the TTP be de-proscribed, it will give the group legitimacy, respectability and stature. The Imran Khan government and the TTP have agreed on a one-month ceasefire which can be extended if both parties agree. Little is known of the deal’s other details, the conditions or demands that were laid down or agreed upon. The Afghan Taliban is said to have mediated the truce deal and is likely to play mediator should the ceasefire move into talks.

There are concerns over the TTP’s demands. Will the Pakistan government agree to its long-standing demand relating to implementation of sharia law in the tribal areas?

Pakistan is at the forefront of efforts to get countries to recognise Afghanistan’s Taliban regime

Holding talks with extremist groups is not necessarily a bad thing; after all, through dialogue it is possible to get militant groups to give up armed struggle, moderate their ideology, outlook and demands, and perhaps even draw them into the democratic process. Several armed groups, such as Nepal’s Maoists, for instance, have renounced armed struggle following talks, and chosen the political path.

It is likely that the Imran Khan government is negotiating with the TTP now as Islamabad has clout over the Afghan Taliban. Pakistan is at the forefront of efforts to get countries to recognise the Taliban regime and de-freeze its financial assets. The Taliban is still dependent on Pakistan, and it is likely that Islamabad will use its considerable clout over the group to get it to deliver a deal with the TTP that Pakistan can live with.

However, there are several reasons why the Imran Khan government’s deals with the TLP and the TTP may not work. The government has not consulted parliament and opposition parties. Nor has the question of engaging in talks with extremist groups been discussed in the public domain. When the terms of secret deals begin trickling into the public domain, they often spring nasty surprises, leading to protests by opposition parties and the public.This could result in the government backtracking on the agreement.

Moreover, the Imran Khan government has swung from one extreme to another in dealing with these groups. Take the TLP, for instance. It was proscribed in April this year. Then, in late October, Information Minister Fawad Chaudhry said that the government had ‘taken a clear policy decision that the banned TLP will be considered a militant organisation’, thus ruling out the possibility of the group being treated as a political organisation. But only days later, the government announced that it had reached a ‘secret agreement’ with the TLP. This is ‘in the larger national interest’, it said.

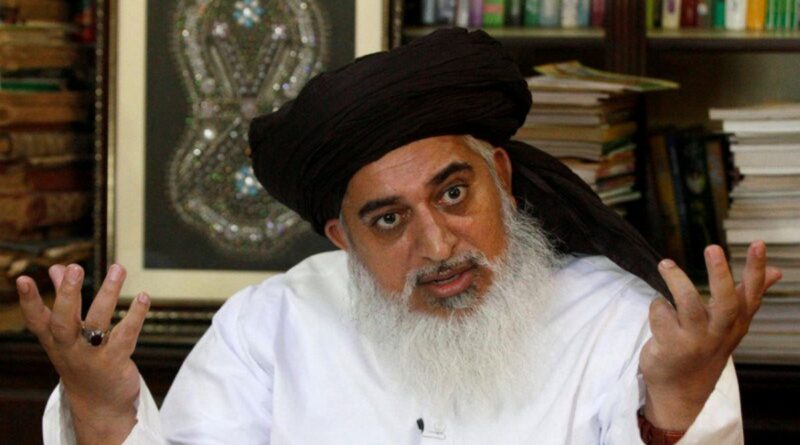

Founded in 2015 by Khadim Hussain Rizvi to campaign for the release of Mumtaz Qadri, who assassinated Punjab Governor Salmaan Taseer for his opposition to Pakistan’s blasphemy laws, the TLP is a far-right organisation of radical Barelvis that projects itself as the defender of Prophet Mohamed’s honour and the guardian of Pakistan’s blasphemy laws.

Its strength lies in its capacity to mobilise tens of thousands of people to participate in its marches and rallies, which paralyse daily life in Pakistan’s cities. The TLP has used this street power to force successive governments to concede to its demands. In 2017, for instance, it forced Law Minister Zahid Hamid to resign. Over the past year its marches were ostensibly to press for the expulsion of the French ambassador to Pakistan and the halting of trade with France as the French Prime Minister Emmanuel Macron had refused to condemn cartoons of the Prophet. It seems to have set aside this demand for now.

The TLP has successfully used its street power this time around to get the ban on the group lifted – a major victory. This will enable it to contest elections again, which it did in 2018. Although it failed to win any seats to the National Assembly, it won two seats to the Sindh provincial assembly. It also performed better than the Pakistan People’s Party (PPP) in the Punjab assembly elections.

In May this year, the TLP again contested elections, even though it had been proscribed only a few weeks earlier. It came in third after the PPP and the Pakistan Muslim League-Nawaz (PML-N). Significantly, it performed better than Imran Khan’s Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf.

The TLP’s popularity in Punjab is rising and its electoral performance can be expected to grow in the coming years. It can be expected to win seats in future elections.

Parties including the PTI and the PML-N are said to be considering the TLP as an alliance partner. The question is, will it moderate its ideology and rhetoric, as do several parties looking to secure the votes of a broad spectrum of voters? Or will it persist with its hardline ideology to radicalise Pakistan’s political mainstream? Given the group’s history, the second scenario seems more likely.

Dr Sudha Ramachandran is an independent analyst based in Bengaluru, India. She writes on South Asian political and security issues and can be contacted at Sudha.ramachandran@live.in